Daisy

quarter-finalist of Eurobot 2003

Daisy was an alternative robot prepared for the contest Eurobot 2003. Daisy was significantly simpler than its sister Dana and again it turned out to be the most critical point. Daisy ranked at the 7th place which is quite an achievement for such a well known international competition.

Overview

Daisy was based on the triangular chassis from the previous robot

Berta. The same motors with 20:1 gearboxes were

used. Also the encoders from PC mouse were the same. The control board was

replaced with a simpler version based on a microcontroller AVR AT90S8535, which

worked very well already for our old robot Alena. The

main advantages of this chip are its price, availability and freely available

software tools. The main computer was iPAQ, a pocket PC with WinCE operating

system. The flipping mechanism, dual-cannon and all the other mechanical parts

were created from Merkur (Czech version of Mechano). Finally four servos

handled motion of the various mechanisms.

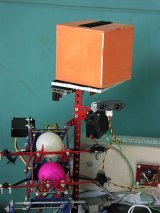

Mechanics

Top view |

The core of the flipping mechanism was an L-shaped hand with two degrees of

freedom. It could either flip the puck or let it go based on its color. The

main advantage of this solution was that the robot did not have to back up or

even stop when manipulating the pucks. The task was then simplified to just finding

some pucks. The L-hand was quite fragile, so we built a cage around it for

protection. Another reason for this cage was bringing down pucks in the vertical

position, and guiding them directly into the hand.

From the left side (this robot had the front given by the pointy end of the

triangle) there was also a small protection barrier against stacking pucks.

Finally this construction also protected sensor Sharp GP2D12 mounted in the

middle of the robot, scanning its left side.

A small holder for the pocket PC became another reinforcement of the robot

frame. It was mounted on the required beacon support. A week before the

contest a double-cannon mechanism was build. It could fire ping-pong balls

against single-colored pucks. The cannon could easily shoot 5-10m, and was

triggered in two steps with a single servo.

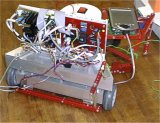

Control hardware

Electronics from the back |

The main board provides almost all available pins. Some of them are

connected through a resistor to an LED indicator, others to a comparator with a

trimmer. Everything is connected using jumpers, so it is easy to disconnect the

LED or the comparator. There are six digital outputs forming tri-connectors

<ground, external +5V, I/O pin>, for easy plugging of the servos. The

analog inputs form a similar configuration <ground, +5V, analog in>, so

many external devices or sensors can be directly plugged by a simple

tri-connector.

The main board contains a socket for an H-bridge L293D. If more powerful

motors are needed, as in the case of Daisy, then an external H-bridge can

be connected.

Many smal board were added later on. There was one board with MAX232 for a

serial communication with PC, various filters for the Sharp sensors, a board for

encoders (it was actually the original board from Berta), and a board for

handling light gates.

Sensors

At the beginning Daisy had only a few of CNY70s for detection of black and

white color. Two of them were build into the L-hand for puck color recognition.

The first sensor pointed up and the second one down, so simple difference of

analog values allowed a very reliable classification (all two-colored pucks

were from inside half black and half white). The other X CNY70s

(originally 3, then 5 and at the end 4) were used for a navigation based on the

color of the floor.

The second type of sensors were two Sharp GP2D12 with a maximum range around

80cm (minimal about 8cm). An extra filter was need for 1kHz noise (the sensor

signal was modulated with 1kHz and it also influenced the analog output). In

the final configuration one Sharp was mounted in the middle of the robot

pointing left, used for mapping of pucks, and the second was mounted just below

the beacon support for detection of the enemy robot (or better its

beacon).

From the big set of digital inputs only two were used - one for the starting

cable and second for a light gate of a puck detector. There was also a second

light gate detecting pucks entering the Merkur construction and one micro-switch

for a collision detection, but both were disabled in the final code.

PC

The “brain” of Daisy was iPAQ, a pocket PC with WinCE operating

system. This computer talked to the main board via serial line (a

communication speed was set to 36400baud). All decisions were made by the iPAQ

only. This configuration turned out to be very good. It was possible to write

a program directly in C++ and compile it on a standard PC or laptop. It was

easy to debug and modify various settings. When the program was finally stable

enough, you could just swap the cables and re-compile the same program for

iPAQ. In 98% the program run immediately without any need for a change.

There were couple differences which made our lives harder:

- the compiler for iPAQ did not support templates and exceptions in C++

- you will get different results for iPAQ if you use floats instead of doubles, while our laptop internally always computed in doubles

- our program for iPAQ did not support text output on the screen

- iPAQ runs on 200MHz, which is less than ordinary PC, and mathematical operations with floating point are implemented with a software emulation

Software

The main board

The program for the main board was written in C. We used proved technique of

access to all low level variables. Daisy had following outputs from iPAQ: PWM

for the left and right motors, positions of four servos, watch dog, digital

outputs. The inputs were: timer, encoders status, digital inputs, analog

inputs. All communication was block oriented. The main board was always

slave and the iPAQ master. Each block was protected with an extra

checksum. The main board had only one task - directly realize commands from the

master. There was one exception: if the time given by the watch dog elapsed

turn both motors off. This feature was very useful for the moments when a cable

was disconnected or the program was waiting on a forgotten breakpoint.

Simulation, reality, log…

Software for the iPAQ was “slightly” more complex. It grew

bottom-up, so the very first thing that was implemented was an encapsulation of

the communication with the main board. This was handled by a class

AbstractHardware, which had exactly the same parameters as the structure

sent over the serial line. It had only one extra pure virtual function

synchronize. It probably does not have any sense to go into more

detail, so let's rather talk about what it was good for: this solution allowed

very simple switching inputs and outputs of the whole program. It could be

direct communication with the AVR chip or it could be a simple simulator or a

binary log file. The program would not recognize it.

I consider this trinity: simulation, real run and run from log file, to be

such a critical point, that I decided to dedicate a whole paragraph to it. Why?

Ok, when you are at the very beginning, you usually have nothing or nothing

working. It is necessary to make sure, that the mistake is not in the

software, so you just test it with a simulator first. I am not talking about

any complex software package costing several thousands dollars. I mean just two

lines of code, which for given PWM generate output on encoders in given

direction. That's it. If you want something better then you can for example

compute robot position, and draw it on the screen, but it is not necessary. And

if your control program sends some non-senses you can debug it with simple

stepping through the code.

When your program works fine with a simulation you can let it run in

reality. It should not happen any more, that your robot will start in the

opposite direction than you expected and that it will badly hurt itself in the

collision with the radiator. If so, then you should probably fix the simulator

and the cycle repeats. It is a good idea to check that the robot really

received the commands you sent. This is the reason to use log-files. Generate

them always and generate their name automatically. Only this way you

will not loose previous, maybe important, log. Also happend just now in reality

may not repeat next x months… until it happens at the very worst

moment – believe Murphy .

End of the lecture – this was the core of Daisy we could build on. I would

say that Daisy belongs to category RobotXP, where this trinity is similar to

unit tests in eXtreme Programming. And what was it all good for?

Robot strangely limped loosing its position almost one square, but then somehow corrected the error.

The log showed that the analog input number 7 connected to CNY70 for the

floor color detection was always 255. One pin of the sensor was broken and it

needed a replacement. This happened just two hours before departure for

the Istrobot competition.

Daisy behaved so well that I decided to make a demo for a friend of mine. He pulled the starting cable and the robot started to twist and hit both sides of the playing field many many times. During 90 seconds the robot did not leave initial four squares so its score would be 0.

The log looked ok, but the program using the data from log file (here I would stress

that it is very critical that the program running from log must behave

exactly the same, i.e. for the same inputs it has to generate the same

outputs, otherwise it is completely useless – it is also a good idea to check this

detail and be careful with random generators, float vs. double arithmetics, timers etc.)

immediately after the start positioned the robot at negative coordinates outside the

playing field. The error was in the initialization and emerged only if you waited long

enough before you trigger the starting cable and in the first 50ms you pushed the robot

a little. This bug did not show up for several months, but with the log file it

took just a couple seconds to find it. Can you imagine looking for it without the log?

I can't.

Robot started, but during the whole match it did not turn a single puck although the light gate detected them (LED indicates interruption of the beam). Is the power regulator fried or did we mess up the code for the main board when we extended it from two to four servos?

The log showed … that the problem is in the software so it is

not necessary to check cables and connections. Simply, servos did not receive a

command to move. Why? A bad initialization again - this time in the module for

handling pucks. Usually I ran hardware check program before the main

application, but I did not do it this time. So there was a huge number in the

variable m_lastTimeCmdChanged and the module could not change the hand

position until this time has elapsed.

Is it enough or should I add a few more experiences with the Sharp sensors,

which see pucks at any distance depending how you look at them…?

Strategy & modules

When the essentials work everything is much simpler. If not then it is

necessary to simplify everything and it may start to work. This is probably our

global strategy but I did not plan to talk much about this one now. An example

could be a task to follow a path. Daisy moved nicely but slightly in curves.

We tried various types of controllers but in the sharp turns it always panicked

a little and did not correct the error in time before the next turn. Solution?

We decided to use the same controller as Dana. Shortly, Daisy moved straight

only, and when it wanted to turn, it stopped and turned in place and then

continued straight again. There were much less parameters to tune and worked in

short time quite well…

Another software package directly used from Dana was GMCL (Genetic Monte

Carlo Localization), a module for navigation using CNY70 and known ground

color. If the robot moved without collisions then this method kept its

position within +/- 5cm and approximately 10 degrees of angular error. This was

enough for the puck collection but as we found out later it was insufficient

for precise shooting.

The puck flipping and the navigation worked independently. Module

Flipper checked only if a puck is present, and if so then, based on its

color, it flipped or let it go. There had to be a short pause between each

command, approximately 1-1.5 sec so that the servos manage to move to the

required positions. This worked quite well if the robot moved forward but it

sometimes failed when turning right or backing up. This concept was not

changed/improved for the contest.

The motion planning evolved from fixed path to a map integration and shooting balls.

The final version which was used for all matches on Eurobot 2003 used this program:

SeqEle seq[] =

{

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.45, 0.45),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.4, 0.45),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.3, 0.6),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.3, 1.05),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.4, 1.05),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.3, 1.05),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.3, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.4, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.3, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.9, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.9, 0.45),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 0.9, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 1.5, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 1.5, 0.45),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 1.5, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.1, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.1, 0.45),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.1, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.7, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::ASK_MAP),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.7, 0.45),

SeqEle(SeqEle::GO_TO_WAYPOINT, 2.7, 1.65),

SeqEle(SeqEle::RESET_MAP)

};

The robot was supposed to move from the starting position (the bottom left

corner had coordinates 0.0 0.0) and to move parallel to the long sides of the

field. Concurrently the mapper scanned all pucks on the left side within 60cm.

The command ASK_MAP then produced a list of new goals so that Daisy

started collecting all pucks on the left side. Most of the pucks were dropped

but they no longer were in their initial positions.

After cleaning of the first two rows Daisy moved to third row, reset

its map (RESET_MAP) and repeated the same maneuver. Similarly it

handled the fifth and sixth row. This pattern was then repeated in the

perpendicular direction, parallel to the shorter sides.

Collision detection

The strategy just described also integrated collision detection. If the

upper Sharp sensor saw the second robot in the way to the current goal position

(WAYPOINT) it switched to the next one in the table. Similar steps were

performed when the collision was detected from the virtual bumper.

The dual coverage of the field in two different directions (in the time

limit 90 seconds Daisy could not do much more) had an advantage that if the

second robot got stuck somewhere Daisy finished unclean part in the second

direction.

Weaknesses and problems

Detection of the enemy robot definitely did not work for 100%. It would be

necessary to remember at least the last scan, because the upper servo scanned

the environment only once a second. The main reason we did not implemented

anything more sophisticated was, besides lack of time, bad experience with the

fixed Sharp for mapping the pucks positions. It turned out to be critical for

the mapping to scan the whole scene and then look for a global minima. It was

impossible to decide from a single measurement if the puck is in distance 60cm

or 25cm (moved from the axis of the sensor beam). We expected very similar

problems and in France there was no spare time for a sufficient testing and

analysis.

Another weak point was a recovery from localization failure. If a heavy and

strong robot hit Daisy then GMCL typically lost the track, and the pre-planned

path could not be realized. This for example happened in the last match with

Supaero, when after the collision Daisy just remained in one corner hitting the

field boundary. It would be necessary to detect this situation, and start to

move without the knowledge of the position or self-localize again. We had an

idea for relatively simple algorithm: if the lower Sharp sensor does not see

any obstacle but it should see the side of the game area then the robot is

lost. It worked relatively ok, but we did not test it sufficiently and we did

not have any strategy without knowledge of position ready, so we did not use it

at the end.

Conclusion

Daisy was another robot from category RobotXP (this is my term, so do not

try to look it up in an encyclopedia ), which with a plenty of luck

managed to reach its potential life top. Daisy is also one of the robots you can

build yourself so we hope it can be also a small motivation for you…

.

If you have any questions or comments –

let us know.